What can wartime recipes teach us about food security today? Assistant Professor Mark Teo and his team turn to the past to imagine a more resilient, homegrown future for Singapore’s food system.

Mark Teo never understood his grandfather’s love for sweet potato porridge. The gooey, sloppy dish seemed unremarkable, even unpalatable. "My grandfather lived through World War II. Sweet potatoes grew easily and were readily available, as such, it was a staple food for most people during the war. Sweet potato porridge continued to be a staple in his diet for the rest of his life," explained the Assistant Professor from SIT's Business, Communication and Design cluster. He is also the Vice-Chair of SIT's Sustainability Education Committee.

Now, as Asst Prof Teo dives deep into his research into sustainability and food security, he thinks such simple food, grown humbly, easily, and almost imperceptibly, in tropical backyards could be the secret to Singapore’s food security.

How Singaporeans of the past filled their tummies during tough times offers useful pointers for the country’s future, according to research by Asst Prof Teo. “It is the concept of innovation out of scarcity – when we don’t have something, we are forced to adapt and create something new. It is also about recognising and leveraging what we have readily and easily available,” he shared.

Humble roots, big impact: sweet potatoes like these once fed a nation in crisis – and could help secure Singapore’s food future. (Photo: Unsplash)

From Dystopia to Food Utopia?

Understanding wartime diets, marked by resourcefulness and rationing, can reveal valuable insights into resilient food systems and adaptive dietary practices.

Beyond traditional farming and emerging urban agricultural practices such as rooftop gardening and indoor vertical farms, how might we grow food at scale and in a decentralised manner?

These ideas emerged from a concept paper in September 2024, titled 'Examining the Resourcefulness of War Time Recipes to Develop Future Urban Food Systems for Singapore'. The paper was co-authored by Asst Prof Teo, Associate Professor Jeffrey Koh, Head of the Design Factory, and – somewhat unexpectedly – Chef Russell Nathan.

The paper drew not only from reference books, but also Chef Nathan’s expertise as the former head of a Michelin-starred restaurant. “Jeffrey and I like food, but we are by no means experts. Chef Russell brought a different knowledge set to the group, helping us identify and classify foods,” Asst Prof Teo said.

The project began with imaginative conversations between the two professors about dystopian scenarios, which led to the problem of food shortages and supply chain collapses during such situations.

"As designers, we like to imagine and project future challenges. This allows us to work backwards and figure out potential changes and chart a route towards a preferred future," said Asst Prof Teo, who holds a bachelor’s in architecture and a master’s in environmental management. "We thought about doomsday scenarios and looked at current food technologies like alternative proteins," explained the fan of 'Dune', a dystopian movie series from which he drew inspiration.

This was especially useful as the team studied concepts like alternative ingredients sourced locally and readily, a key finding from wartime diets.

People then would substitute scarce ingredients for those that grow easily and contain high nutritional value to cope with resource scarcity.

Chef Russell (left) and Asst Teo (right) right before their presentation. (Photo: Asst Prof Teo)

Reconnecting with Food Production

While the project revealed that Singapore has many endemic edible plants, such as kangkong, tapioca, and sweet potato, which are reliable local food sources, getting people to include these in their daily diets is another challenge.

“How might we change our food system and help people adapt their diets and eating habits and vice versa?”

Asst Prof Teo believes that one solution is to get Singaporeans more involved in food production. In a country where only 1 per cent of land is dedicated to farming, its residents have grown increasingly disconnected from growing food, he observed.

It does not help that the country imports over 90 per cent of its food, leaving its people even more divorced from food production.

“One of the easiest things we can get people to do is to start growing food at home, which can be an interesting project,” he said. He added that this practice is far more sensible than relying on produce that travels long distances, citing blueberries from Zimbabwe as an example of how far our food can come.

“It’s not about taking away other choices from imported food but adapting our diets to include ingredients that can be readily available,” he explained. “More than anything, it’s a mindset shift.”

To this end, the team hopes to improve public education surrounding food security through a board game which aims to grow awareness through play. Set in a dystopian world, the game will teach players how to substitute ingredients in well-known local dishes and to forage for food. Currently in development, the game is slated for release in the second half of 2026.

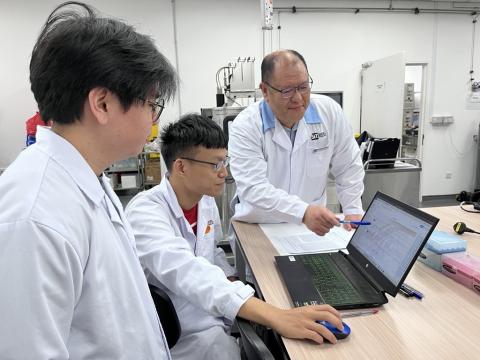

Hydroponic systems in schools give students hands-on experience with sustainable food production. (Photo: Unsplash)

Schooling Singaporeans

Singapore still has some way to go when it comes to sustainable food production, he said, but he is hopeful. “We are moving in the right direction. Nowadays, you see a lot of gardens in schools that have been made accessible and comfortable for students.”

Allowing them to interact with food production technology like hydroponics and engage with the harvest to validate their efforts is key, he said.

There is much to learn from the elderly, who are often experienced in growing food and participating in community gardens.

“Connecting the two generations – young and old – can help to pass down not only knowledge, but also a lifestyle and culture of cultivating food,” he said.

Just like he did with his grandfather.

![[FA] SIT One SITizen Alumni Initiative_Web banner_1244px x 688px.jpg](/openhouse2025/centre-professional-communication/sit-teaching-and-learning-academy/sites/default/files/2024-12/%5BFA%5D%20%20SIT%20One%20SITizen%20Alumni%20Initiative_Web%20banner_1244px%20x%20688px.jpg)