Placing first in two popular hackathons is a feat achieved by a rare few. Applied Computing student Li Yiming stood out by grounding every idea in a clear understanding of what his clients truly needed.

It’s not often that a student wins two hackathons back-to-back. It’s even more impressive when he does so with different teams. Li Yiming, a second-year Applied Computing student at SIT achieved this in a matter of weeks this year, leading his teams to clinch top spot in Morgan Stanley’s Code to Give in August and JP Morgan’s Code for Good in September.

In Morgan Stanley’s Code to Give, a five-day virtual hackathon, Yiming’s team developed Reach Connect, a donor engagement platform for Project Reach, a Hong Kong based ,children’s non-profit organisation, that aims to turn one-time donors into recurring supporters. Meanwhile for JP Morgan’s Code for Good and with another set of teammates, he built an AI-powered matching and administrative platform for United Women Singapore (UWS), a women empowerment organisation.

“I didn’t go in expecting to win. I recognised some competitors who are great programmers, but I didn’t know my teammates at all before the events. It was a good experience overall,” shares the 24-year-old.

The Winning Formula

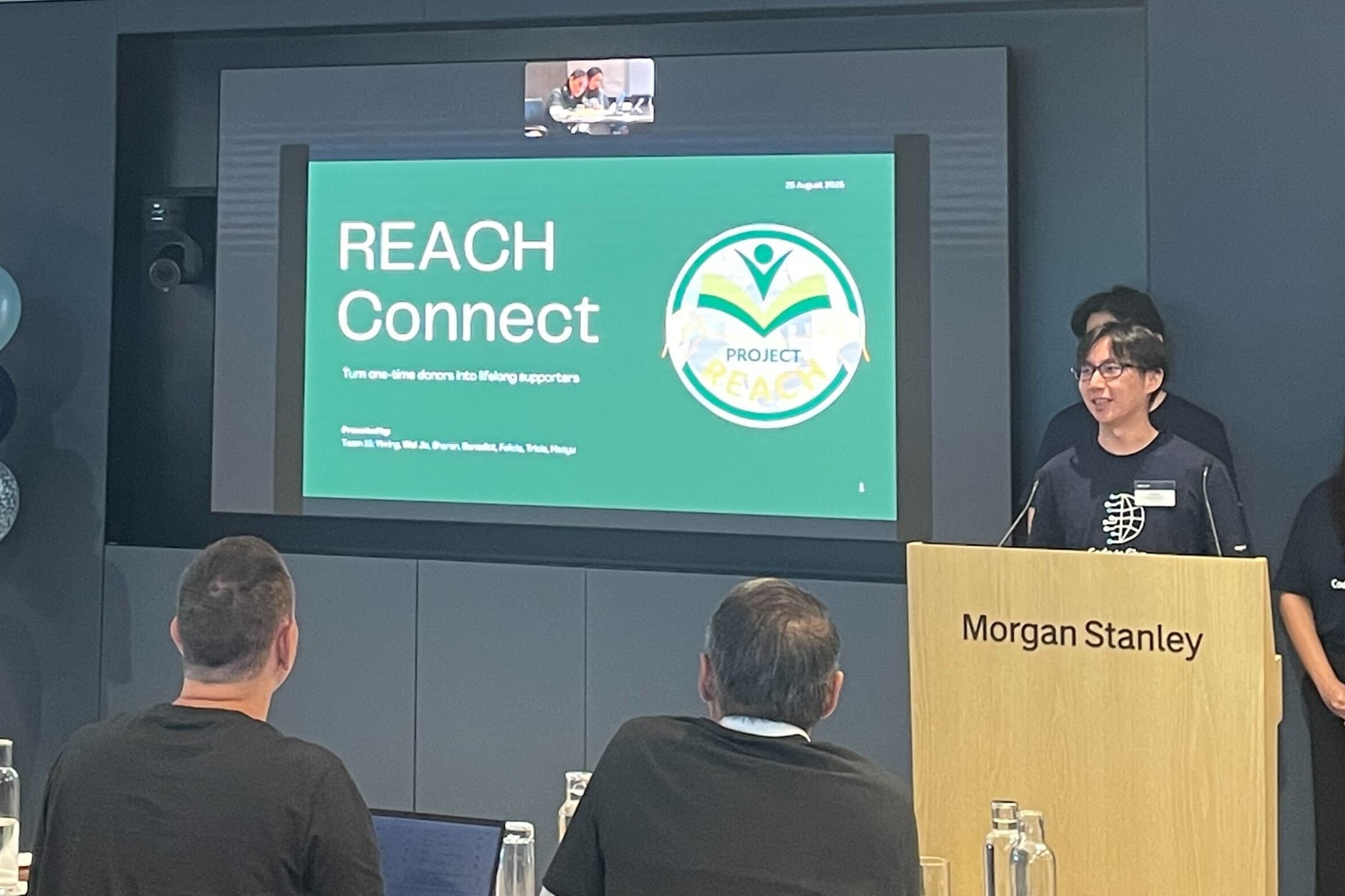

Yiming, fifth from left, together with his winning team at Morgan Stanley’s Code to Give hackathon. (Photo: Yiming)

What set Yiming’s teams apart from the competition wasn’t necessarily speed or technical prowess (though they had both)—it was slowing down enough to ask the right questions before writing a single line of code.

“I’ve learnt that taking the time to ask the right questions early on helps the team stay focused and aligned on what really matters.”

Yiming speaks from experience. He did his Integrated Work Study Programme (IWSP) at Accenture, a global technology and management consulting firm. His IWSP experience taught him that the most viable solutions begin with a clear understanding of an organisation’s pain points and the root causes behind these pain points. By understanding the initial problem, he could pinpoint where the real gaps lay, allowing him to create solutions that were not only innovative but genuinely useful for the client.

“A client might ask for trendy features like gamification or leaderboards,” he explains. “But it’s important to step back and try to understand what’s driving that request. Are we solving the real problem, or just adding features for the sake of it? It’s crucial to distinguish needs from wants early on,” he adds.

As team leader, Yiming encouraged his teammates from various local Institutes of Higher Learning to dig deep into what their hackathon “clients” truly needed. For the Morgan Stanley Code to Give challenge, they submitted over 20 thoughtful questions to Project Reach — a level of curiosity that stood out among the teams.

What resulted was a donor-focused solution with breadth and depth that directly addressed Project Reach’s most pressing concerns.

Yiming, top row, second from right, together with participants in JP Morgan’s Code for Good hackathon (Photo: Yiming)

“After the first win, I brought that same approach to JP Morgan’s Code for Good,” he says. “Even though we only had seven hours, we spent extra time talking with United Women Singapore before starting on the solution, while most teams had already begun coding.”

Yiming’s eventual win was a clear sign that impactful engineering begins with curiosity and a genuine understanding of what success looks like for the client.

“While I enjoy the technical side, my strength lies in connecting business needs with technology,” he reflects. “Having some domain knowledge in finance and user experience design helped me form a clearer picture of the problems we were trying to solve. And of course, I was fortunate to have great teammates; our skillsets complemented one another’s.”

Experiential Learning Makes the Difference

Yiming is seen presenting Reach Connect, a donor engagement platform for a children’s non-profit organisation Project Reach. (Photo: Yiming)

The hands-on education at SIT gave Yiming an additional edge, where students develop practical experience from working with the latest technologies in the field.

“Every term, we build real – products that we can see end-users using in the market such as using machine learning for facial recognition payments, or developing educational games and creating personal stock-screening tools. Hackathons are not much different – understanding user requirements, developing a solution for commercial viability – but just with a much tighter deadline,” he quips.

In a high-pressure hackathon environment where friction commonly occurs among teammates, Yiming points to an unexpected source of preparation: his involvement with the SIT Investment & Commerce Club. The student-run group regularly discusses finance and investments, topics that can stir strong opinions.

As a result, Yiming has become a seasoned diplomat—not just unafraid to speak up in a group but able to do so with tact and sound reasoning.

“Investing can be emotional, but we learn to make logical arguments about why certain stocks are overvalued or undervalued. It trains you to communicate clearly and respectfully.”

Yiming nevertheless takes a practical tone when it comes to thriving in a competition brimming with programming whizzes. “Having a grasp of full-stack development means you can step in wherever the team needs support,” he says.

“And above all, I believe the best engineers are those who keep asking the right questions and focus on delivering meaningful solutions.”

![[FA] SIT One SITizen Alumni Initiative_Web banner_1244px x 688px.jpg](/openhouse2025/openhouse/centre-professional-communication/openhouse/sit-teaching-and-learning-academy/centre-professional-communication/directory/sites/default/files/2024-12/%5BFA%5D%20%20SIT%20One%20SITizen%20Alumni%20Initiative_Web%20banner_1244px%20x%20688px.jpg)